“Our heritage and ideals, our codes and standards – the things we live by and teach our children – are preserved or diminished by how freely we exchange our ideas and feelings – Walt Disney“

Fellow travelers… Welcome back to this exploring world filled with wonderful moments of my ever exciting expeditions. As you all know, my explorations had covered the natural wonders, ancient architectures and serene spiritual centres of incredible South India. Now, its time to change my path, not my destiny. Taking the leap into the unknown is scary, but you aren’t the first person to travel the world. You aren’t discovering new continents or exploring uncharted territories. So, come with me… together, we will see and relive those mesmerizing moments, i had in my latest trip to the infamous land of Northeast India – “The Nagaland” .

A land filled with myths and mysteries, inhabited by vibrant people zealously guarding their culture – warriors, headhunters, dancers, singers, mountains, hills and valleys, forests and grasslands – all these form the portrait of Nagaland the moment the word is uttered. When you heard stories about Nagaland, You may feel scared and nervous, the first time. But, from extreme mystery to hosting a globally famous cultural festival, Nagaland has come a long way over the years and etched a name for itself in the list of world’s best destination spots.

A 21st century creation of Nagaland is the Hornbill Festival, an event which is now getting known globally. During Hornbill, which takes place on the first week of December, the entire Naga culture is showcased in full splendor at the Kisama village of Kohima district. The Nagaland government welcomes one and all to this mega event for a preview of what the state has to offer in terms of culture, traditions, tourism interest and industry.

Contents of Part 1

- Nagaland

- Who are Nagas ?

- The Hornbill Festival of Nagaland

- Story of ‘My Long Journey’ to Kohima

- Exploring the cultural extravaganzas of 19th Hornbill festival 2018 (Includes only the 9 tribes of Nagaland, selected alphabetically)

- Other interesting traditions, competitions and art performances in Hornbill festival

‘Nagaland’

Guidebooks are useful for a general overview of a destination, but you’ll never find the latest off-the-beaten-path attractions in them…

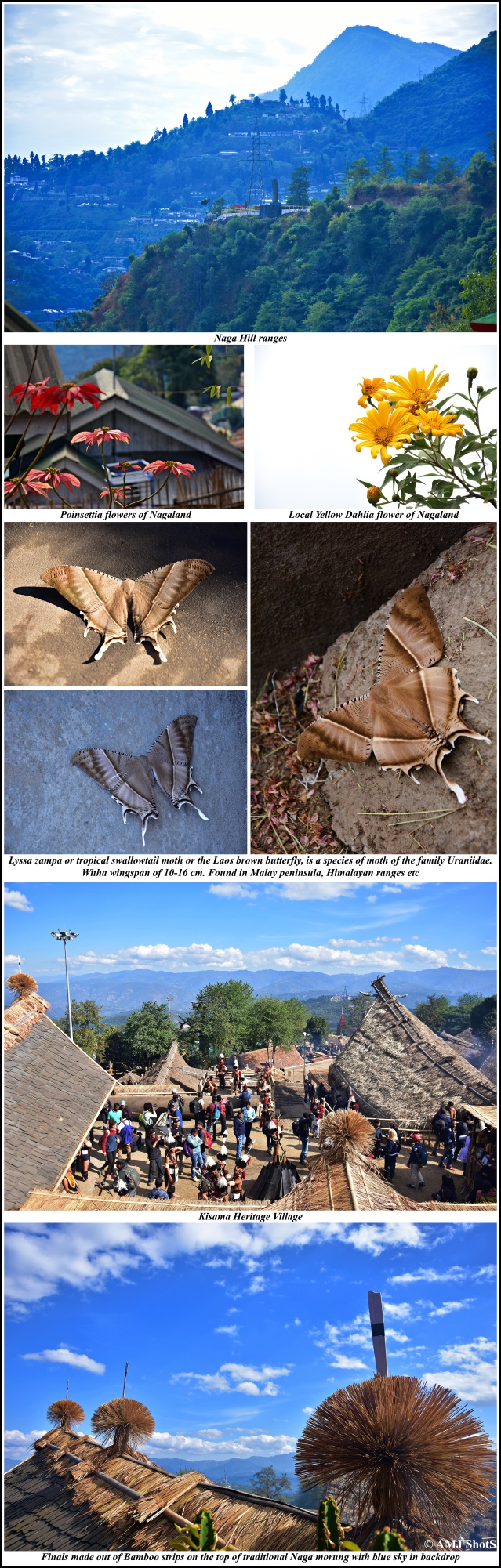

View from the top of Naga heritage village at Kisama, Kohima district.

Nagaland – One of the ‘Seven Sister’ states at India’s remote northeastern corner, came into being on 1st December, 1963 as the 16th state of the Indian Union with Kohima as her capital. With a geographical area of about 16,579 sq km, she shares her borders with Assam in the North and West, Myanmar and Arunachal Pradesh in the East and Manipur in the South. Topography of the state is nearly all hilly, the highest peak being Saramati (3841 m) in the district of Kiphire. Many rivers cut through this mountainous terrain, like sharp swords slicing through rocks, the main ones being Dhansiri, Doyang, Dikhu, Milak, Tzu and Zungki. The climate of Nagaland is nothing but perfect. With pleasant summers where the temperature rarely rises above 31 degrees and winter temperature averaging 10 degree Celsius, making it a “perpetual holiday destination”.

Blue sky with puffy clouds shadowing the green Naga hills… The hilly areas have a cool and bracing climate; the scenery in many parts of the hills is breath-takingly fine and several writers claim that for sheer grandeur and beauty it is unmatched.

The best months to visit Nagaland are between October and May, when the landscape wears a green carpet and flowers light up the skies with their bright hue. Rhododendrons (State flower) and Orchids cover the landscape of Nagaland and one cannot miss them even as he is driving or trekking the challenging terrain. Traditionally the Naga people have been hardcore hunters, but awareness in conservation has resulted in common sighting of endangered birds and animals. The rare Blyth’s tragopan (Tragopan blythii) is a resident of Nagaland and can be observed in plenty. Another important species that you need to look out for is – The Amur Falcons (Falco amurensis).

Not many states of India’s ethnically rich Northeast perhaps as vibrant and colourful as Nagaland is. This is a lustrous land of once brave warriors who fiercely protected their land, natives who has held on to traditions amidst changing times with great pride of their respective ancestry. For a true Naga nothing matters more than the word-of-mouth, nothing matters more than their tradition which has taught them to extend warm hospitality to a guest who knocks at their door with an openness of being. With changing times tigers may not dance across the Naga terrain, Hornbills still do, when they woo.

‘Who are Nagas?’

Fierce headhunters from the wild….. oh, no!… That isn’t exactly correct. I can explain…..

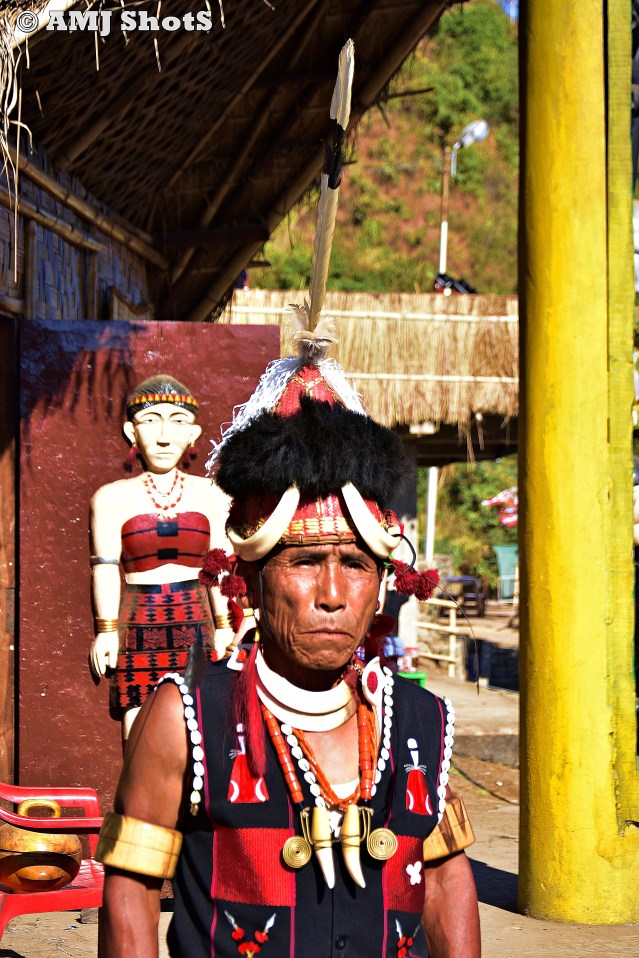

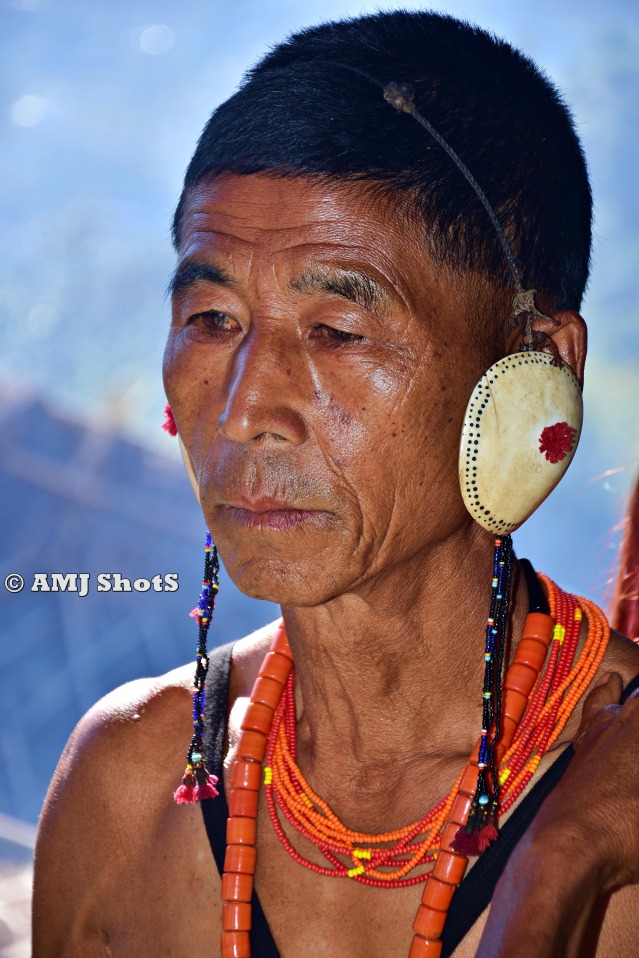

‘Sangtam Naga’ in front of his Morung.

Naga traditions and Cultures are the two main conduit pipes through which one can smell the odours of and peep into the social, political and religious systems of the people and their societies. The Nagas are the ones whose conduit pipes were sealed to the outsiders until the white missionaries changed their hearts thoroughly in the earlyparts of the 20th century and thereby opened up their sealed covers to a few white writers. The term ’Naga’ applies to all people living in compact area between the Brahmaputra river and the Chindwin river. The area of present Nagaland state is only 16,579 Sq. Km. and the Naga areas in Manipur State measure 15,519 Sq. Km. Many Nagas such as Konyaks, Khiamniungans, Yimchungers etc. are living in the Naga Hills of Burma, the exact areas and population of which are not available. Most of the Naga villages stand at a height of 1000-2999 meters. The name Nagas of “Nagaland” as used here, has only one connotation – the present state of Nagaland and not the entire Naga areas including those which are outside Nagaland.

Origin

The origin of the word “Naga” has been a source of much debate among different scholars. The two largely accepted view points are taken from the etymology of the word “Naga” and its varying connotations in the Burmese and the Assamese languages. The basic groups of human race are Caucasoid, Mongoloid and Negroid. The Nagas belong to the Mongoloid group. The hypothesis that the Nagas must have came from the sea coast or at least seen some islands or the seas is strengthened by the life-style of the Nagas and the ornaments being used till today in many Naga villages. The Naga being left undisturbed for such a long time, have retained the cultue of the most ancient times till today. The fondness of Cowrie Shells for beautifying the dress, and use of Conch shells as ornaments (precious ornaments for them) and the facts that the Nagas have many customs and way of life very similar to that of those living in the remote parts of Borneo, Indonesia, Malaysia, etc. indicates that their ancient abode was near the sea, if not in some islands. The long war-drums hewn out of huge logs also feature very much like the Canoes so common with the islanders. It is also a fact that the Nagas ate almost all living sea creatures. It is difficult to say as to when this word came into existence. There are various theories as to the origin of this name ‘Naga’. It is surprising that the Nagas, who are so conscious of the meaning and connotations of their personal names, do not have any meaning for the word ‘Naga’. It is therefore, quite probable that this name ‘Naga’ is not a Naga origin but named and popularized by outsiders to give an identity to those tribes. Different scholars, basing their surmises on the Naga art, material culture, language tonals etc. have theorized that the Nagas have had some links with Indonesian and Malaysia, they belong to the Tibeto-Burma family; are the first stage migration group from North-West China; they constitute a return group of migrants from the Polynesian islands, etc. However, these theories are remotely inferential theories and in the absence of substantive evidence these theories remain inconclusive. In spite of various theories with more or less logical evidences provided for to find out the origin of word Naga and publicized over the centuries is a guess work and it is known to nobody. No Naga living in Nagaland and Manipur state can give a substantial evidence and say as to why they are called Naga. Definitely the word ‘Naga’ is given by the outsiders to these people. But what is the key to this name is nobody knows.

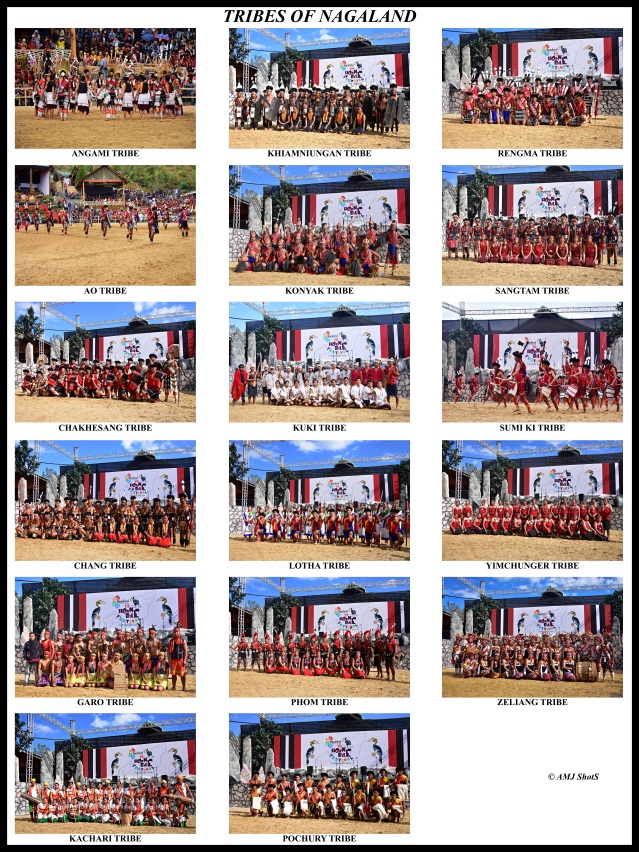

Tribes of Nagaland

Officially there are 17 main tribes in the state of Nagaland. The are Angami (Kohima district), Ao (Mokokchung district), Chakhesang (Phek districk), Chang (Tuensang district), Garo (Dimapur district), Kachari (Dimapur district), Khiamniungan (Tuensang district), Konyak (Mon district), Kuki (Peren district), Lotha (Wokha district), Phom (Longleng district), Pochury (Phek district), Rengma (Kohima district), Sangtam (Tuensang and Kiphire districts), Sumi (Zunheboto district), Yimchunger (Tuensang and Kiphire districts) and Zeliang (Peren district).

Language

Language is the principal means of communicating culture (a word which itself commonly embraces the entire life of a people. The language of a people provides the means by which they express their way of perceiving things and of coping with them. In the entire North-Eastern states about 8 million tribal people speaking hundreds of different languages. In Nagaland, the Nagas speak their own tribal languages and dialects which vary widely from one another even though their languages, from sufficient evidences, are derived from the same cognate stock in the remote past. Today Nagamese (a hotch-potch of Assamese, Nepali, Bengali, Hindi), Manipuri, Hindi and English are the media of expression among the Naga tribes as well as the outsiders. English is not only the official language of Nagaland but also the medium of instruction and examination in Schools and colleges.

Naga culture and oral history flourished without any written script of their own. Yet they had an effective medium of communication and records that have been preserved for many centuries through the oral tradition based on deep-rooted and time-tested foundations. Any oral narrative of traditional history, origin and migration of the

people (tribe, clan, individual, etc.), formation of the village, events of war, peace, festivals and so on are transmitted by word of mouth from one generation to another through songs, poetry, ballads, prayers, sayings, stories and tales or as public oration when the situation demands. Through such means youngsters were trained

not only to learn but to master them.

Main Occupation

The bulk of the communities in the North-East are still at pre-agricultural stage of economy depending largely on shifting cultivation. Agriculture and animal husbandry have been the basic occupations of the Nagas since time immemorial. Agriculture, both terrace and shifting cultivation is the Primary basis of agrarian economy of the Naga people. All Nagas tribes are primarily agriculturists. Their main crop is rice, millet and maize. Besides, they grow vegetables, like pumpkins and gourds, the latter for use as containers also. The most striking difference between the Angami and their neighbours on the north is their cultivation of wet-rice while other tribes of Nagaland such as AO, Lotha, Rengma and Zeliang cultivate by “Jhuming” (that is, by clearing land and growing crops on it for two years and then allowing it to return to jungle), the Angami has an elaborate system of terracing and irrigation by which he turns the steepest hill sides into flooded rice-fields, and in dealing with his cultivation, this terraced cultivation and ‘Jhuming’ must be treated separately.

Religion

Baptist Church inside the Heritage village at Kisama.

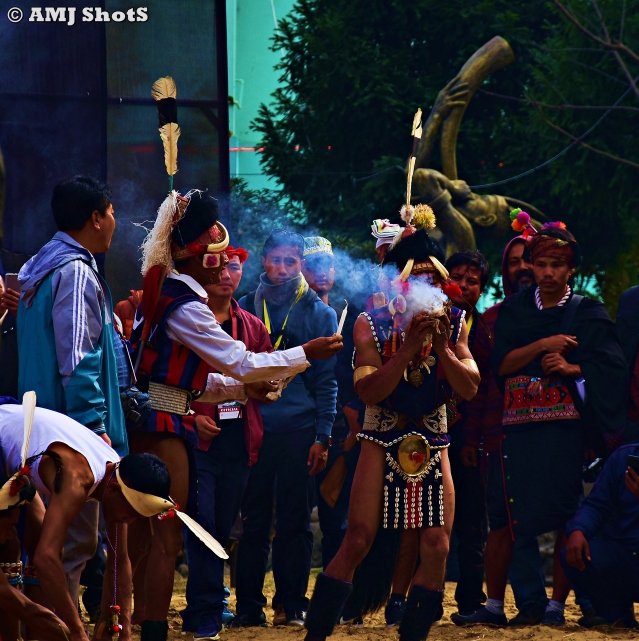

Forms of belief and evolution in the tenets of faith of a people play an important role in the history, growth and development of the people. If we look in to the early history of the Nagas and pay our attention to the traditional beliefs and forms of worship of these people, and how these have changed over the different stretches of time, we can catch an illuminating glimpse into the evolving psyche of these people. Religion, whether in its earliest form of animism or in the modern form of Christianity, has played a vital role in the history of the Naga people. Thus, any view of the Nagas, whether sociological, economical or historical cannot be complete without an effort at tracing out the changing religious patterns of these people. The early Naga tribes believed in spirits. These spirits were teneficient as well as maleficient. A very, important part of the Naga belief in all these spiritual beings was the large number of “gennas”, or ceremonies, for the propitiation of these spirits. These gennas varied from tribe to tribe and from region to region. The intricate system of beliefs and rituals of the Nagas suggests that their religion was a mixture of Animism and polytheism. The two great religions of India – Hinduism and Islam never reached the Nagas, and did not bring them under their influence. Thus, the religion of the Nagas was branded- by the early Christian missionaries as ‘Animism’. It is now a little over one hundred years since the Nagas accepted Christianity as their lives.

Culture and Arts

An average tribal may be shy of contact with the outsider but when the ice is broken he takes no time to deal with any one on terms of equality. Nagas without exception are Xenophobes. They have always been suspicious of all outsiders. One of the first characteristics that strike a visitor to the Angamis, Rengmas and Zeliang is their hospitality. Both men and women are exceedingly good-humoured and always ready for a joke. Their staunchness, too, was proved in France (During second World War) where men who had volunteered to face the utterly unknown and served well in labour corps”.

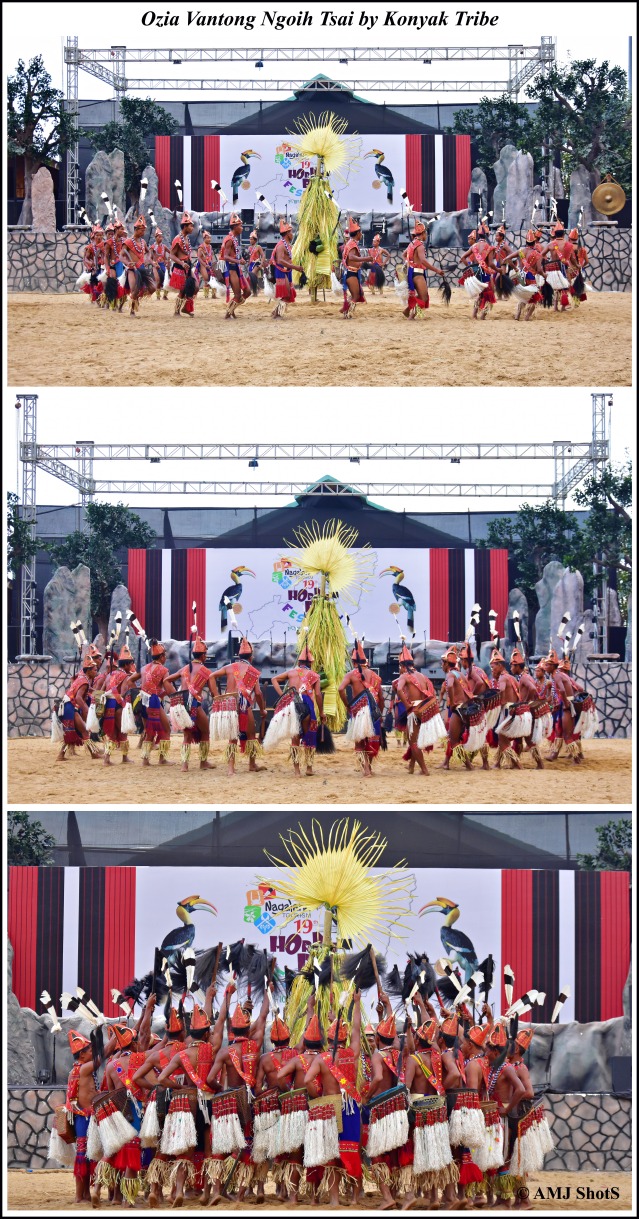

A Zeliang Naga performing Honey Bee Dance

The art of dancing, partially, was eroded when Nagas accepted Christianity. Nagas usually dance in groups, and sometimes the whole village joins in during their festivals. Dancing enlivens their social life. It promotes unity and brotherhood and looks charming with their colourful ornaments, costumes, cowries, ivory, scarlet hair and brilliant hornbill feathers. These dances now a days take place during their important festivals, including Christmas and New—Year, marriage ceremonies etc. All Naga tribes are full of folklore. They are found of seasonal songs, solo, duet and choric, songs in praise of ancestors, warriors and other heros are the most popular. All Naga tribes are full of folklore.

Headhunting Days of Nagas

Wooden sculpture of a Konyak headhunting warrior with muzzle loading gun

All Nagas love hunting, both for the sport it gives them and for the meat it brings, and a petition for success in the chase finds a place in most ceremonial prayers. Sambhur and barking deer are the animals most frequently hunted by Nagas. Besides this Nagas were champion of head-hunters. The Nagas were head hunters as late as 1858. It was not a rare adventurous action. They collected heads as our children collect stamps. In fact, the practice of head-hunting which existed at different times in various regions of the world, usually originated in the superstition that the human head contains the ‘Soul-Force’. This was believed to govern the rise and fall of a community and thought to be transferable. The slain man had to belong to a different village if his ‘Soul—Force’ was to benefit his killer. An increase in population, cattle or pigs, better crops and other material improvements were believed to demand as accretion of ‘Soul-force’. When the ‘Soul-force’ diminished, the tribes were promoted to embark in head-hunting expeditions to replenish this intangible asset. Head-hunting was a part of every day life of the Nagas, and to a great extent, conditioned their life in the villages. Successful headhunters enjoyed the privilege of wearing special dresses and ornaments. They were distinctively tattooed and accorded with coveted social status. However, inter-villages and inter-tribal clashes were the main cause as well as effect of headhunting in those turbulent days. During the headhunting days, the prettiest girl in the village would consider herself fortunate if she marry the man who had taken the most head during a raid. He automatically became a leader and was respected by the entire village. However, since the embracement of Christianity, things have been changed and animism with head-hunting has been pushed to the background. It became part of Naga history only.

Customs

Naga society is patriarchal, and as such, inheritance is always in the male line. A woman can possess property but she cannot inherit it. All sons equally share the patrimony. Although each Naga tribe has distinct characteristic of its own, they have certain features in common. They are truthful, honest, brave and believe in hero-worship. The Nagas have no prejudice against any kind of food. If a non-Naga refuses their food or dislikes their way of living, they cannot take a liking to him. They will at once feel that he cannot be one of them, if he criticizes or shows his dislike of their way of life, or in any way suggest inferiority of their status. If the objective is to induce them to better modes of living and thinking, it can only be achieved by gradual stages, the first of which is to assure him of one’s sincerity of purpose and not by force or disapproval of these ways of life.

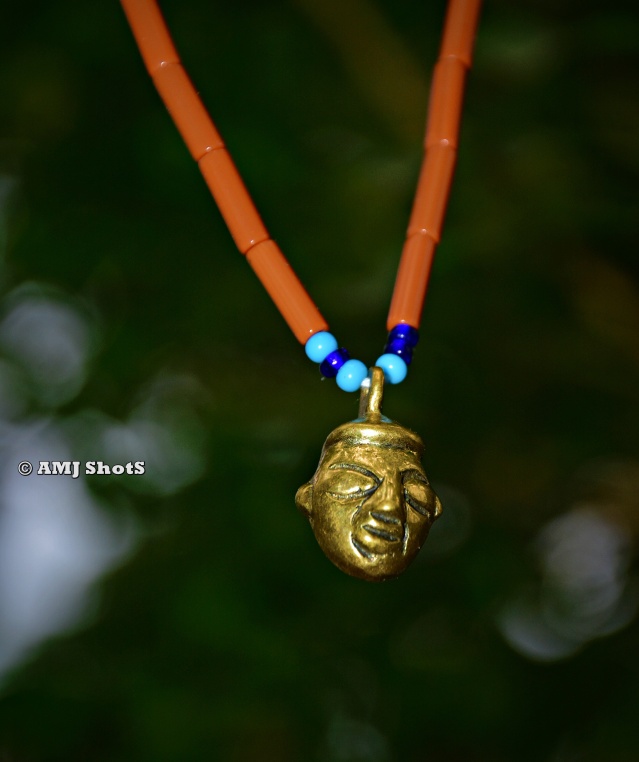

Dress and Ornaments

A Phom lady in her traditional attire with a Warrior, who is holding a muzzle-loading gun

The most prominent item of Naga dress is the shawl. It is different for every tribe and, besides, there are varieties and sub-varieties in every group. In the past it was possible to identify, by simply looking at the shawl of the wearer, the tribe he belonged to and occasionally even the group of villages he came from, his social status etc. Nowadays, with the spread of education and civilization almost touching the tribal life. Almost all tribal youth imitating the western style dresses. Every Naga youth has a old or new Jean pant to wear whether it is a villager or urban youth. In spite of this transition, the wearing of shawl is still exist. The cowrie decoration is quite popular among the Nagas. The ornaments are simple but pretty. A necklace of beads is generally worn round the neck. The beads may be made of some kind of stone or shelIs. Dancing dress is yet more colourful. Men’s head dress is a coronet of hornbill feathers, circle in shape, the feathers positioning a convex canopy frame. However, these coronets vary in form according to the status of the wearer. They are fastened at the head by the white cotton robes, held out by a circular shingle.

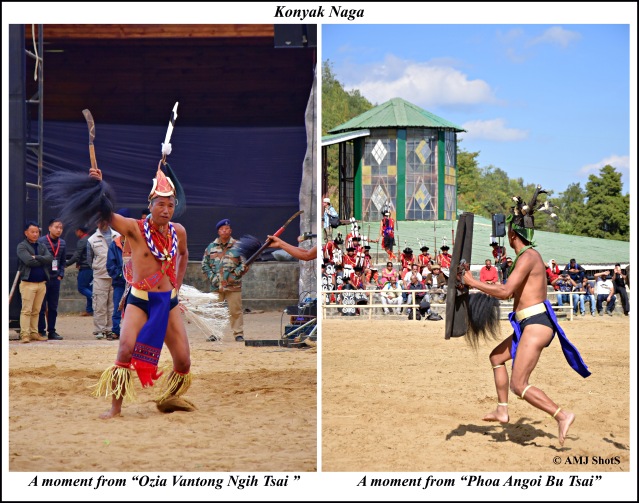

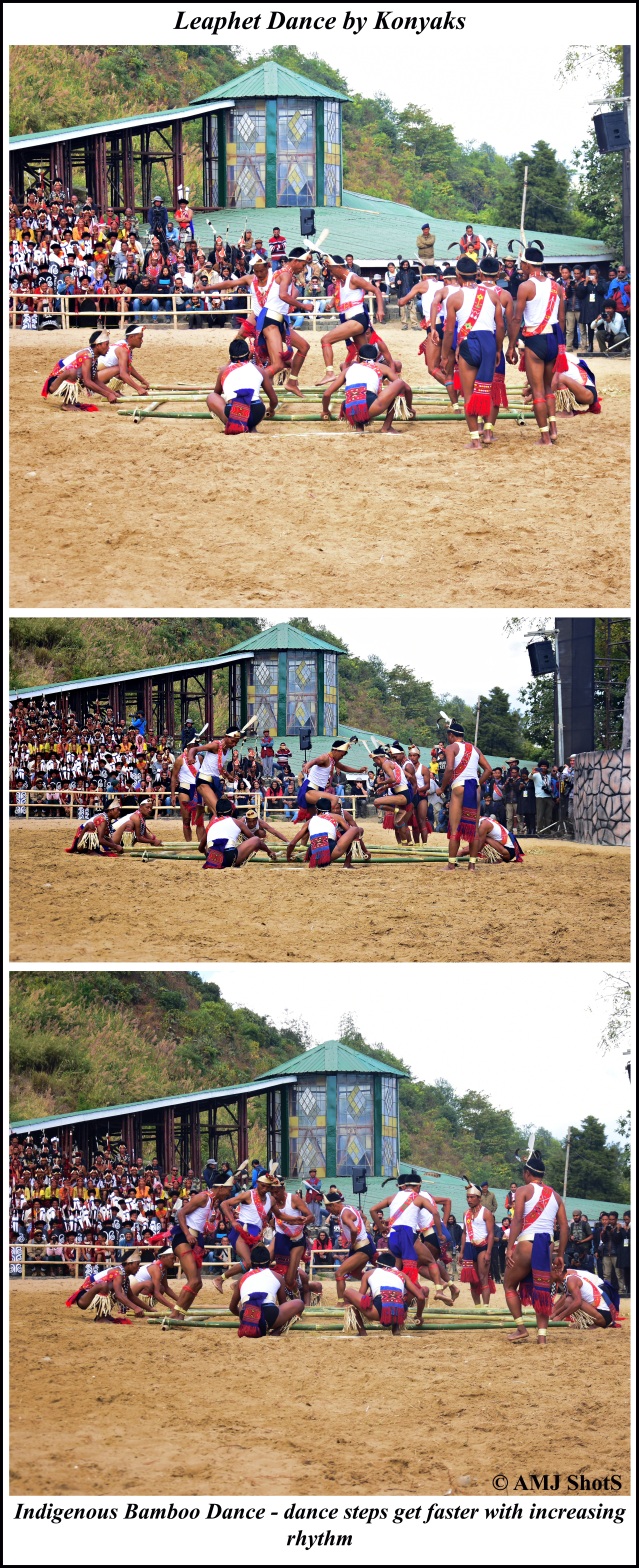

The men in Nagaland perform War Dance with an outburst cry and humming tune. It can be said, this dance form mocks war scenario by involving dangerous war movements. A single wrong step could ruin an entire act, it’s martial and athletic style requires a performer to whirl his legs while keeping the body in an upward posture. Besides the traditional attire worn by the performers are simply unique. Thus a blend of vibrant hues, great music, cultural dance and delicious food, the week-long Hornbill Festival celebrates the traditional values of Nagaland’s 16 tribes. This colourful festival is also one of the major crowd-pullers for the state and falls in what is believed to be the best time to visit the state. Not many are aware of the fact that the Hornbill Festival is named after a bird mentioned earlier – “Tragopan Blythii”.

“The Hornbill Festival of Nagaland”

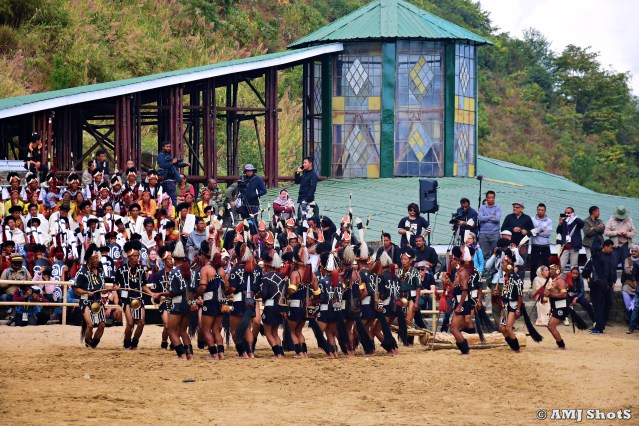

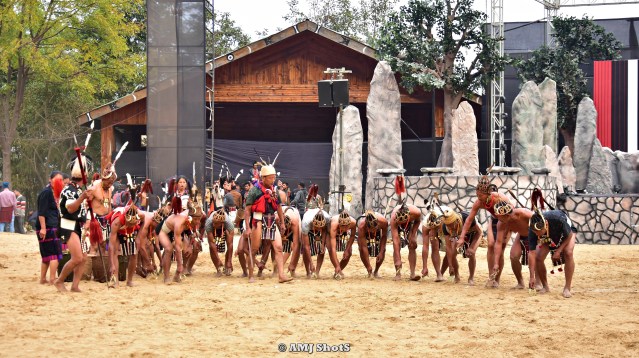

Angami tribe performing Melo Phita Dance in the main arena of Hornbill festival 2018

Spirits, fertility, social bonding and purification are the key elements that form the the essence of the Naga festivals – the custom that each tribe follows, translates into a festival. These traditional events, combined with life in the rural areas, are exceptionally engaging and distinctive. All of them are annual events with fixed dates; hence, before visiting Nagaland, the interested traveler can arrange his or her calendar accordingly. The first festival takes place in January and the last in December – no matter what the season is, some festival is always around the corner.

It was in the year 2000, that the State Government desirous of promoting tourism embarked upon an ambitious project with the help of BASN (Beauty and Aesthetics Society of Nagaland), to exploit the cultural assets of Nagas, through a week long festival to coincide with the celebration of Nagaland Statehood Day on 1st December. Thus, the inception of the Nagaland Hornbill Festival so named in collective reverence to the bird enshrined in the cultural ethos of the Nagas to espouse the spirit of unity in diversity.

The Hornbill Festival takes place between the 1st December, which happens to be the Nagaland Formation Day, till the 10th of December, annually. Recently, seeing its grand success and achievement at attracting tourists from far and wide from across India and abroad, the Hornbill Festival has been extended by another three days till the 10th of December. The aim of the festival is to revive and protect the rich culture of Nagaland and display its extravaganza and traditions. Organized by the State Tourism and Art & Culture Departments of Nagaland, Hornbill Festival showcases a melange of cultural displays under one roof at a model village built at Kisama, a western Angami location situated 12 kms away from Kohima, the capital of Nagaland. History abounds in every nook and corner of the terrain here. Kisama falls on the historically famed Kohima-Imphal Road, now a busy highway cutting through Angami hamlets connecting Dimapur with Manipur, once the theatre of the fiercest of battles fought between the defending British forces and an advancing Japanese army during World War II.

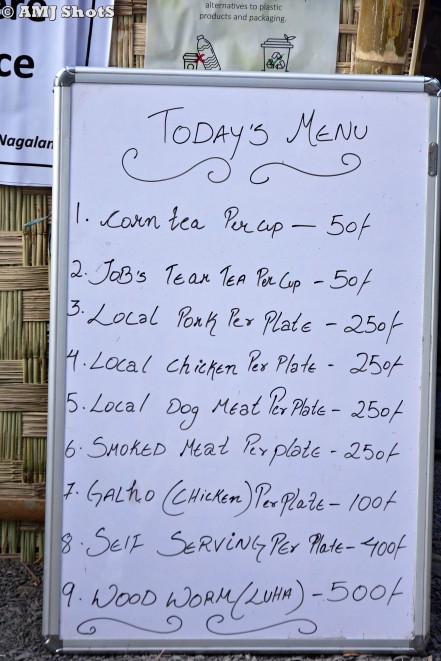

Dotting the hillside of the Kisama Heritage Village, the location of the Hornbill Festival each year, are these hubs of warmth, food and easy camaraderie where visitors can seek out a Naga meal with sticky rice, smoked pork and pickled bamboo shoots, each morung offering its own varieties of meat and spices and Zutho, their fermented rice beer. As temperatures dip with sundown by 4.30 pm, visitors huddle around the coal and wood fires in the morungs, tall bamboo tumblers of beer in hand, as musicians start tuning up for the evening performance at the amphitheatre.

For visitors it means a closer understanding of the people and diverse culture of Nagas, and an opportunity to experience Naga food which is no less varied, as are the songs, dances and customs of the place. This colourful festival is a certain paradise for a foodie, particularly if one happens to be a non- vegetarian. Nagas love to feast and feed, and at Kisama one can try all kinds of Naga traditional food and also watch them being made during the Hornbill Festival days. Tourists are welcomed warmly to the traditional huts of each tribe showcasing respective traditions. For those interested, one may seat with the youths and elderly people of the tribes alike and interact with them. One can also take part in various contests such as Naga chilly eating, pork eating besides traditional games and other traditional competitions.

Heritage Village, Kisama, Kohima District

The nomenclature of KISAMA is derived from two villages namely, Kigwema (KI) and Phesama (SA) and MA which means Village, on whose land the Naga Heritage Village is established and commissioned by the State Government of Nagaland.

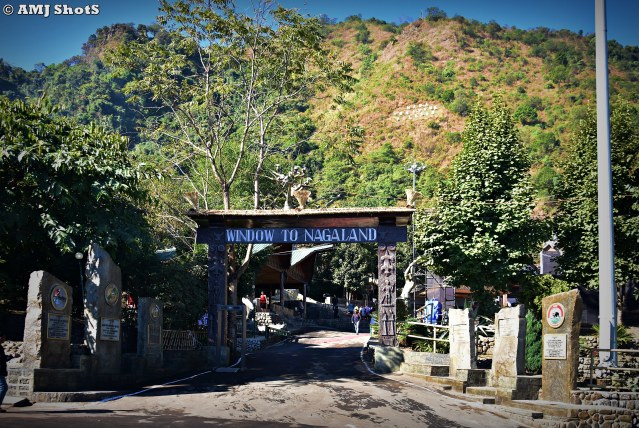

Entrance Gate of the Heritage village at Kisama

The Heritage Village was set up with an objective to protect and preserve all ethnic cultural heritages by establishing a common management approach and comprehensive data base for perpetuation and maintenance for promotion of tourism. It also aims to uphold and sustain the distinct identity of dialects, customs and traditions of all the ethnic tribes of Nagaland.

Kisama Heritage village and surrounding Naga hills…

The Naga heritage village placed on the foot hills of a magnificent green valley

The Main Arena of Naga Heritage Village.

Contrary to what many people believe, the actual site of Hornbill festival is located at about a 20-minute drive from Kohima (if the traffic isn’t brutal, 12 kms from Kohima town) in the Kisama Heritage Village. And those not bitten by the idea of staying in the capital city of Kohima, like me, should consider staying in the town of Kigwema (the next village at only a walking distance from Kisama) to avoid bleeding unnecessary time in the traffic. Compared to Kisama, which more or less offers a crowded and bustling city experience, Kigwema is, moreover, less-crowded, laid back and provides all necessary comforts for a tourist. Buf if you want to experience the night carnival in Kohima town during hornbill days, you should consider staying there…

Shots from the surroundings of Kisama Heritage village.

Heritage Complex, Naga heritage village at Kisama

The Heritage Complex consists of a main arena with central stage and a cluster of 17 house of each tribe created in the indigenous typical architectural designs and concepts with significance. The tribal house is also called “Morung or Youth Dormitory.” Colorful life and culture are a vital part of the 17 officially recognized Naga tribes. They are different and unique in their customs and traditions. These customs and traditions are further translated into festivals. Songs and dances form a soul of these festivals through which their oral history has been passed down generations.

Entrance Gate of Hornbill Festival Main Arena.

Main Arena with VVIP Rostrums, Central stage and Audience pavilions…

Hornbill Tree – In recognition of the State bird and as a tribute to the ‘festival of festivals’, placed on the occasion of 15th Hornbill festival, 2015. The majestic hornbill is a Nagaland emblem which represents loyalty, because of the female bird staying in the high nest and relying on her male to feed her. In the past, the right to use hornbill feathers had to be earned, feathers were not for sale, and only those that excelled in warfare received the honor to decorate themselves with the feathers. The Naga tribes recently realized the damages they have done on the species, so they stopped hunting them and now protect them instead. It could be already too late thou to avoid total extinction.

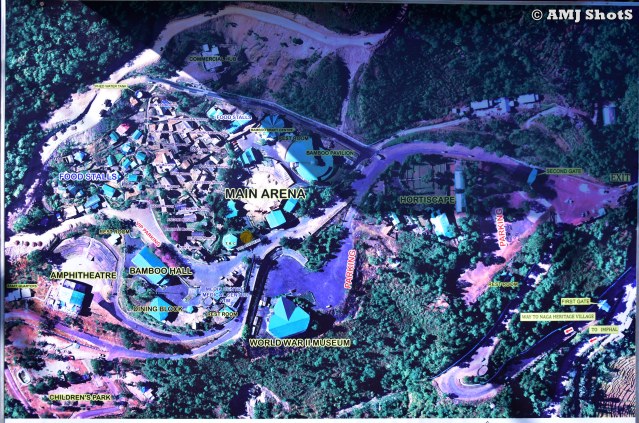

The Heritage Complex also house World War II Museum (World War II Museum that houses relics from the 1944 battle of Kohima, which first put Nagaland on the global map), Bamboo Heritage Hall, Bamboo Pavilion, Kids Carnival, Horti-Scape, Food Courts and Stadium for Live concerts, Naga Idol, Beauty Pageant, Fashion Shows, etc.

Second World War Museum

Dodge Power Wagon – Exhibited in front of the Second World War museum, which was used during the Great Battle of Kohima by British military forces.

Baptist Church in front of Naga Heritage village at Kisama

Bamboo Pavilion with the bamboo heritage hall. This pavilion comprises numerous stalls selling a plethora of items such as handicrafts, tribal ornaments, ethnic food items, Naga dresses, artifacts and souvenirs.

An exhibition of Naga Terriers

Wooden sculptures of a Naga warrior with a tribal woman, standing in front of their traditional hut

Inside of a traditional Naga hut with household equipments and utensils

Stalks of Corn seeds hanging from the ceiling – Inside a traditional hut of Nagas.

Map of Naga Heritage Village, Kisama

Altogether, this festival highlights include Traditional Naga Morungs exhibition and sale of Arts and Crafts, Food Stalls, Herbal Medicine Stalls, Flower shows and sales, Cultural Medley-songs and dances, Fashion shows, Beauty Contest, Traditional Archery, Naga wrestling, Indigenous Games, and Musical concert.

Story of ‘My long journey’ to Kohima

As a traveler from South Kerala, a journey to Nagaland wasn’t that easy, especially when you wanted it to be cost effective. My plan was to spent 7 days in Kohima, from December 2 to December 9 and a 4-day train journey was needed to reach, the only available railway station in Nagaland state, Dimapur. So, in total, the entire trip lasted for 14 days. Being Indian railway as the only option for me at that time, i booked a sleeper ticket in Chennai – Dibrugarh express, which can take about 60 long hours to reach the Dimapur railway station.

Traveling up to Chennai in Guruvayoor – Chennai Egmore express, on 29th November was really a smooth journey. No real hardships in that Journey. But on the same night, that Dibrugarh express leaving the Egmore station, shocked me, with the worst overcrowding I can remember each and every moment of that hectic journey, even today. The sleeper compartment, where more than 150 people are crammed into a space fit for just 72. Bodies dripping sweat, satchels welded to the arm and voices raised to holler at those stepping on their toes: the compartment was filled with migrant workers from Northeast at Chennai itself. For the first few hours, i couldn’t even touch the floor of my compartment because berth i reserved was side upper and also the compartment got packed so tightly. Those migrant workers were going to their homes for spending the upcoming holidays. There was no concept of personal space in crowded compartment like this. What made things fun was that, as soon as you talk to a passenger it turns into a group discussion. It was crowded and noisy throughout the journey. Sometimes even an entire market will pass through that crowded space. How it happens?… Nobody knows that!

For the first 2 days, i was so tensed because of security issues. As my trip was solo, i needed to be feel secure in every moment of it. There were some precious cargos like camera, its gears etc in the bag. That’s the reason, i was worried and couldn’t even shut my eyes properly during nights. The wash basins and toilets were so dirty as people who use it, most of them don’t even bother to flush them. Oh! that was hell of a journey. The only positive thing happened in that train was getting acquainted with a brother from Assam, who is currently working in the oil fields of Tamilnadu, Mr. Debabrat. He, too was going back to his mainland for spending the vacation with his family. By the time train reached Dimapur railway station, i was really tired and needed to reach Kohima, so fast.

Dimapur Railway Station – The only available railway station in the state of Nagaland. The Dimapur district also houses the sole airport in Nagaland with scheduled commercial services to Kolkata, West Bengal, and Dibrugarh, Assam.

Dimapur-Kohima road wasn’t very good in shape and took about 4 hours for just a 76km distance. During winter, daylight in this part of India is moreover very limited and often gets dark before 5pm. driving from Dimapur to Kohima turned out to be a nightmare, because of the poor road condition. The road was under construction transforming a seemingly narrow dirt-track into a four-lane highway, and with that, changing everything bit of a beautiful green into a dusty yellow. You have to hire a private cab or find taxi to arrive at your final destination – Kohima. Luckily, i got a share taxi and it costed me 500 rupees (normally 300 for a person) because of the bulky luggage with me.

Taxis of Kohima

Permits for Nagaland

As you must already be knowing, Indian tourists need to get Inner Line Permits (ILP) for Nagaland. Interestingly, the same is not required for the foreigners (in an effort to encourage tourism). The international tourist however still have to register themselves at the Foreigner Registration Office once they enter Nagaland. You can get the permit at designated offices in Delhi, Guwahati, or at Dimapur on arrival. If you could not make it earlier, the best way is to reach Dimpaur and visit the DC (Deputy Commissioner) office as early as possible, so that you get it sorted by noon. You need valid ID and photographs. The process is not very strict for tourists and I have seen that they become lenient during the festival as nobody asked for my permit on the road.

Where was I stayed in on those 7 Days ???

As you already know, my plan was to spend a whole week with the Hornbill festival of Nagaland. So, I really needed to stay in Kohima town center and find a budget hotel with optimum facilities.

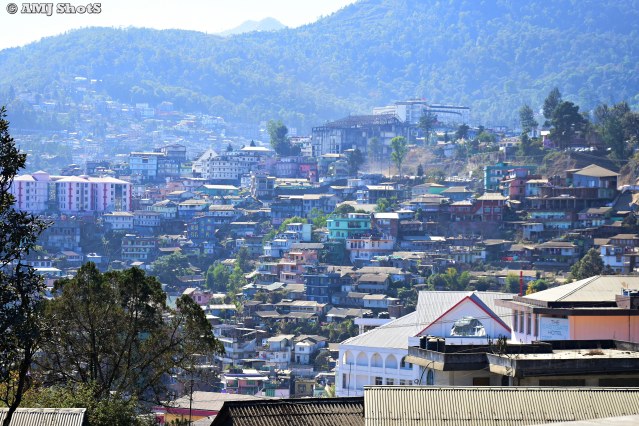

Expanded Kohima Town center in front of the War cemetery. It is the historical landmark, where the infamous Battle of Kohima during 2nd World War took place.

War Cemetery junction of Kohima town center.

Thankfully, because of the contacts and efforts from my uncle, Mr. Mohanan, who has been working in Nagaland as a high school teacher for more than 30 years, the accommodations for the next 7 days was arranged in the Hotel Galaxy, just 200 metres from this war cemetery junction.

Hotel Galaxy – A perfect budget hotel for a solo traveler with enough securities to free from all tensions. Single rooms with TV (almost all hindi, english and malayalam channels are available) cost Rs 500 for a night (with separate toilets)… that’s an awesome pick in Kohima town, especially during these festival days. And this hotel is located just 100 mts from the NSTC bus station (Razhu point)… that’s a bonus. Last, but not the least, a friendly and helpful reception to do whatever you need to have a comfortable stay….

Mr. Shaji, Owner of Galaxy and Evergreen hotels – A friendly and gentle person who is proud in sharing his 33 years of life experiences of Nagaland, without any hesitation to a complete stranger like me. That’s how humble, he is. He is from Kottayam district of Kerala. So communicating with him made me confident enough to travel anywhere in Kohima town.

Razhu Point near the Hotel Galaxy – A 100 mts straight walk towards north will lead you to this point. You will get short bus services from NSTC (Nagaland State Transport Corporation) to the BOC junction in this point. Actually Hotel Galaxy is located mid-way between Old NST junction and Razhu point.

Bus services of NSTC and Taxi services are available in this Razhu point.

A look at the flourishing Kohima town on these Naga hills…

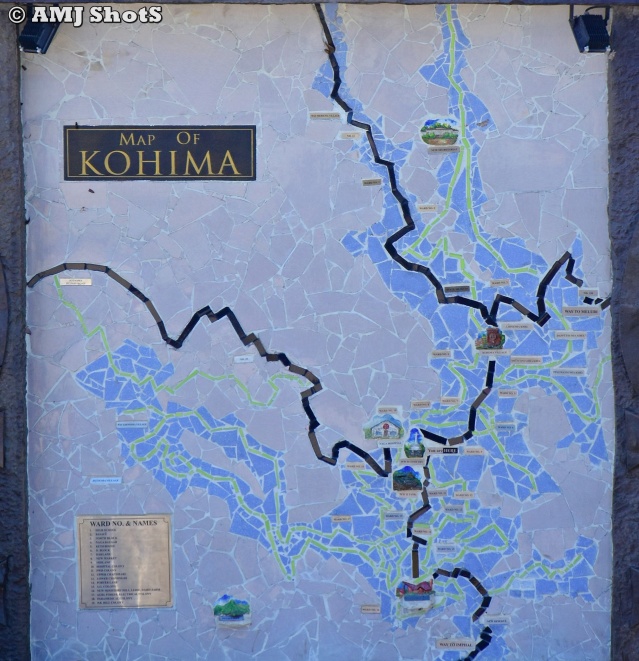

Map of Kohima District

If you want to travel to the Naga Heritage village at Kisama from Kohima town center, first, you need to get a bus service from the Razhu point (Rs 10 per person, end to end service) to reach BOC junction. Then find a share taxi (4-5 persons per taxi and Rs 50 for each) to reach the final destination – ‘Kisama Heritage Village’.

Now I have to get into the details of those mesmerizing moments from the 19th Hornbill Festival 2018…..

Exploring Cultural Extravaganzas of the 19th Hornbill Festival 2018 – Nagaland

Following content focuses on the exciting moments filled with vibrant colours of Nagas, during my expeditions of Hornbill festival 2018 (from December 3rd to 8th, in Naga Heritage village at Kisama). Morung exhibitions and cultural sessions happening in the main arena are the two major things that you need to look out for, while you explore the festival days at Naga heritage village……

Way to Naga Morungs…. If you are interested in photography, visit these morungs in the early mornings, especially before 9am. It can enhance your chances in getting some real life shots…

All the Naga tribes have dormitory organisation known as Morung, a sort of the bachelors’ club where boys are gathered to spend the night. Morung is a vital corporate village institution as a centre of the village ceremonies, arts, music and folk-songs, and field of training, to young men in undertaking duties for the village welfare . In modern term, the village morung is a club-house, a reformation centre, a museum etc. Every village of the tribes like Angamis, is divided into ‘Khel’ of which the boundaries on the ground are exactly known often the ‘Khels’ are called after clans. Each ‘Khel’ had its own ‘morung’. It was a place where no crime be committed. Property could be left lying about in one with absolute safety, for to steal was taboo. An admirable institution, the morung disciplined and educated the young. Now a days ‘morungs’ are no longer seen in the villages. It is, of course, seen in a few villages unused. But it still gives the picture of sanctity, and it is looked as a museum for the present generation. It symbolises the unity of the clan or of a particular Khel. It is now-a-days standing as the pride of the village.

1. Angamis of Nagaland

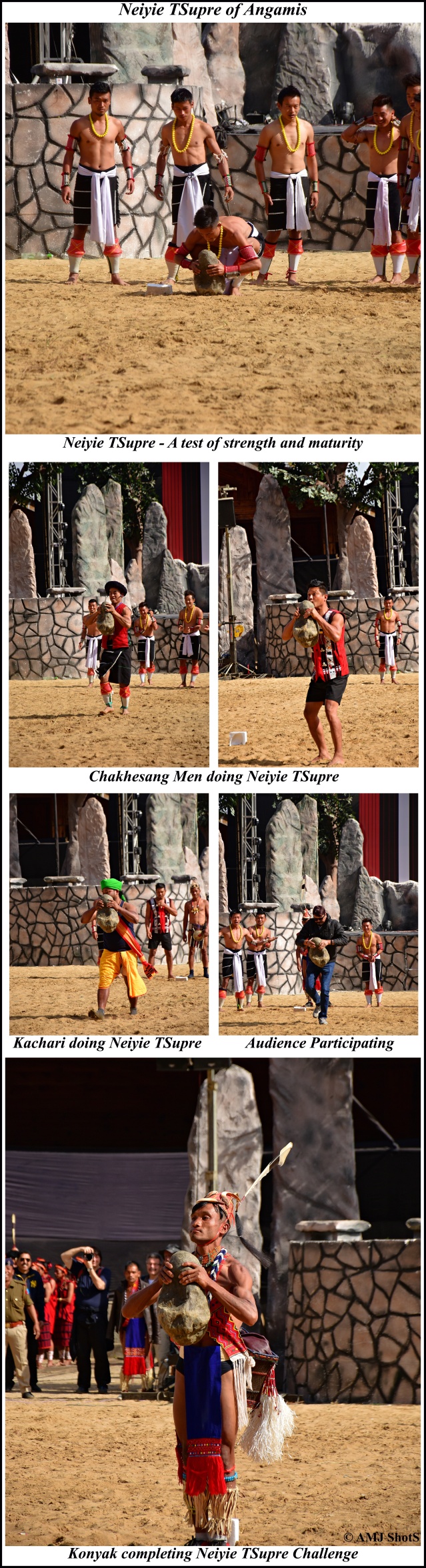

An Angami Naga performing “Neiyie Tsupre” challenge (A test of strength and maturity among Angami youth)

Angami people are the first tribal society to have settled in Northeast India. They are listed as a Scheduled Tribe, in the 5th schedule of the Indian Constitution. According to one legend, the ancestors of the Naga tribes were brothers who lived together with their parents in Khezhakenoma village. When the three brothers spread out, the Angamis came to the present Kohima area. In another legend it is believed that Maikel Stone (Present day Manipur) was the place where ancestors of the Angamis emerged from the earth. Many festivals are also observed by the community according to their culture and tradition. Tendydie, Gnamei, Angami and Tsoghami are mother tongue of Angami Tribes. Tendydie is the one most commonly used. The domination by this tribe of their hills is further understood by their sub-divisions in land, such as Southern Angami (south part of Kohima located on the foothills of Mount Japfu); Western Angami (west side of Kohima) and Northern Angami (northern part of Kohima). The former Eastern Angami have separated and are now recognized as Chakhesang.

Traditional Angami Morung

Angamis prefer to live in the top of hills, which probably has to do with observing a line of sight to invading enemies. Their villages vary in size and observe democracy. Though there’s a village headman, decisions are made with the consent of elders and important persons of the village. Their staple food is rice and drink is Zu (rice beer) which is brewed in every home. The Angamis are also one of the earliest Naga tribes to end their practice of headhunting, which was once a test of bravery, in 1905.

The hill people depend mostly on cultivation and livestock-rearing. They are one of the only 2 tribes out of the sixteen Naga tribes who practice wet-rice cultivation on beautiful terraces carved out on the hill slopes. Due to this labor intensive method of cultivation, land is considered as the most important form of property. Woodcrafts and artworks are the other common means of livelihood, which are performed with great skill. This can be observed in the variety of house doors and clan-gates found in a village. Spinning, weaving, pottery and basketry are also pursued by the tribe, whereas weaving is a must for every Angami woman. The Angamis are also rich in folk-songs, folk dances and folktales.

Sekrenyi (sometimes also called Phousanyi) is the most significant festival celebrated by Angami people. The festival is observed for 10 days in the month of February every year. Literally, Sekrenyi means ‘sanctification festival’ (sekre = sanctification; nyi = feast; thenyi = festival) . The festival falls on the 25th day of month Kezei (according to Angami Calendar) and is celebrated after the harvesting of fields. It is observed in a very traditional and religious manner. The most interesting day of the festival is the thekra hie, when young and old people wearing their traditional dresses sit together and spend the day singing songs, performing dances, have feasts, drinking beer and merry making. All the work ceases during the ten days of feasting and song. It is no wonder that Nagaland is called the ‘land of festivals’.

“Melo Phita Dance” of Angamis – A warrior dance performed by men folk. Dancers form a circle and perform rhythmatic steps in accordance with folk songs.

Melo Phita Dance – This dance is performed as a part of the friendship ritual ‘ Phita thenyi ‘ between the inter-villages of Angami tribe. During this ritual, the friendly villagers hosts each other with folk songs and dances.

Melo Phita Dance – The citizens of one village hosts the guests from other villages, in process of making friendships between them.

Neiyie Tsupre (test of strength and maturity) – In olden times, young lads attempted to carry a stone held above their head without touching their body around a yard to show their strength and eligibility for marriage. Failure to accomplish this was interpreted to mean immaturity.

After doing the test, the Angamis challenge the members of other Naga tribes and audiences to participate in Neiyie Tsupre.

A moment from the traditional game of Angamis – “Khwe Mele Pwe Kejo” , two groups of Angami youngsters will stand opposite and then, throw small cloth balls (made from shawls) and try to hit at the members of opponent team to score points.

Angami men and women folk together performing ” Nyokro Kewa Khwe “ – A song with dance performed during the rice pounding occasions in agri fields near the villages.

Currently, Angami tribes are divided into five major types namely Seventh Day Adventist, Baptist, Pentecostal, Christian Revival and Roman Catholic. Eighty percent of the population of Angamis follow the Baptist, with churches in the Angami region being owned and operated by Angami Baptist Church Council. It is to be noted that there are still some Angamis who follow an animist Pfutsana religion, thus denying to convert to Christianity. Historically, Angami religion was that of tsana (meaning ‘way of ancestors’), which was characterized by belief in spirits. Above all creature, the chief, was Kepenuopfu, who was considered the creator and supreme being of all living creatures. The literal meaning of Kepenuopfu is simply ‘birth-spirit’. The Angamis also had deities as ‘terhoma’ meaning spirits, but when the missionaries came and translated the word terhoma, they termed it as ‘satan’. This made the notion of all the terhoma be considered as evil in the minds of the people, even when the qualities of some of them were definitely benevolent.

2. Ao Tribe of Nagaland

Ao Naga performing ” Tsungremong Dance “

The Aos are one of the major Naga tribes in Nagaland. They are first among all the Naga tribes to embrace Christianity and by virtue of this development the Aos avail themselves to Western education that came along with Christianity. In the process the Aos became the pioneering tribe among the Nagas in many fields. Christianity first entered into the Ao territory when an American Baptist missionary Edwin W. Clark reached an Ao village called Molungkimong in 1872. Their main territory is from Tsula (Dikhu) Valley in the east to Tsurang (Disai) Valley in the west in Mokokchung district. They are well known for multiple harvest festivals held each year.

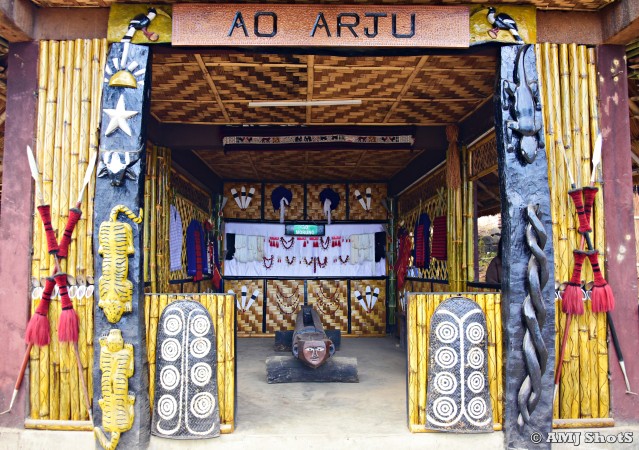

Traditional Ao Morung

Ao Nagas are found in the north-eastern part of Nagaland, mostly in the central Mokokchung District and also a few are found in the adjacent Assam state. Mokokchung, one of the districts in Nagaland, is considered as the home of the Ao Naga tribe. It covers an area of 1,615 Sq km and is bounded by Assam to its north, Wokha to its west, Tuensang to its east, and Zunheboto to its south. The physiography of the district shows six distinct hill ranges which are more or less parallel to each other and run in the south-east direction.

Inside of an Ao Morung – There is a traditional log drum of Ao Nagas placed at the centre.

According to the folklores, the Ao Nagas emerged from ‘six stones’. These stones symbolise their forefathers and that location is named as ‘Longterok’ which means six stones. These stones are still intact at Chungliyimti in Tuensang district. From this village, the Ao tribe moved towards northern region crossing a river named Tzula and settled at Soyim, also known as Ungma today. This was the first Ao Village ever known. After a few centuries, a group of people moved further to the north-east of Soyim and settled at a place named as Mokokchung, or today’s Mokokchung village. Many other Ao Naga villages came into being when people migrated out from this village including Ungma in the later part.

The main annual festivals that were popular in the past are the Moatsu Mong and the Tsungremong. The Moatsu festival is celebrated on 2 May in honour of Lijaba, the creator of the whole earth, to appeal for his blessings in the cultivation that immediately follows after the sowing season. It is celebrated with vigorous singing and dancing, continues the customary practices f making the best rice beer and rearing the best pigs and cows for slaughtering during the festival. The womenfolk, dressed in their traditional fineries, join the men folk in composing warrior songs. Villagers sing songs to eulogize the lovers and the village folk as a whole. the elders encourage the youth to be bold and heroic for defending the villages from enemies, a custom continued from the head hunting days.

The Tsungremong festival or the ‘festival of blessing’ is a celebration for harvesting, which is held during the 1st week of August. Tsungremong, named after the man who started the ritual, is a thanksgiving festival.

Tsungremong Dance of Aos – This dance is performed during Tsungremong festival. The natives wear their colourful traditional garbs, sing traditional songs and perform their ritualistic dances to express their gratitude to god for giving a high yield. The festival also provides opportunities for the budding generations and other villagers to display their skills and physical strength. the festivity is symbolic of a good harvest and members of Ao community gather to thank God for blessing them with a rich harvest.

“Man knows since primitive days that without God, there is no blessing. And Ao Naga tribe has understood it very clearly. This Tsungremong is to particularly ask God to bless and to invoke God’s blessings in one’s life.”

Next one is the “Hornbill Dance of Aos” ……

Hornbill dance performed by the Ao tribe honouring the grand hornbill bird which is regarded as a symbol of valour, faithfulness and noble disposition, much admired for its majestic movements and instinctive alertness. The dance imitate the footsteps of the bird as it feasts leisurely on top of the tree with pride, hoping from one branch to the other selecting and feasting on their choicest fruits.

” Tenem Sungjok or Hornbill dance “ – The Hornbill bird is regarded as bravery, valour and beauty. It is developed in synchronizing with the mystical movements of Hornbill bird. In this dance the forward and backward movement of the dances imitate how bird moves on the branches of the trees. This dance is performed during all the major festivals of Ao tribe. Hornbill dance occupies a high place of honour among all the traditional dances of Nagas.

Now look at the Head Hunter’s Dance of Aos….

Ao Nagas performing ” Head Hunter’s Dance “ with an outburst cry and humming tune.

Head Hunter’s Dance of Aos – It can be said, this dance form mocks war scenario by involving dangerous war movements. A single wrong step could ruin an entire act, it’s martial and athletic style requires a performer to whirl his legs while keeping the body in an upward posture.

Ao Naga performing Head Hunter’s Dance – The traditional attire worn by the performers are simply unique and they carry weapons such as Dao and long spears. The ‘Dao’ is the life-long

companion of Nagas. The weapon consists of a blade about twelve inches long, its breadth being more at the tip (about four inches) than at base (about one inch). The blade is fitted into a wooden handle which is tightly bound with cane or iron. The dao is carried in the holder at the back.

Head Hunter’s Dance of Ao Tribe – Chanting, clapping and shouting of words, thumping of feet, gracefully endowed with traditional headgear and clothes inspires every member of the group and the spectators as well. In order to add vigour to the dance, the performers are garnished in metal ornaments.

Their is an interesting indigenous game played among the Ao nagas – The Go Kart Race...

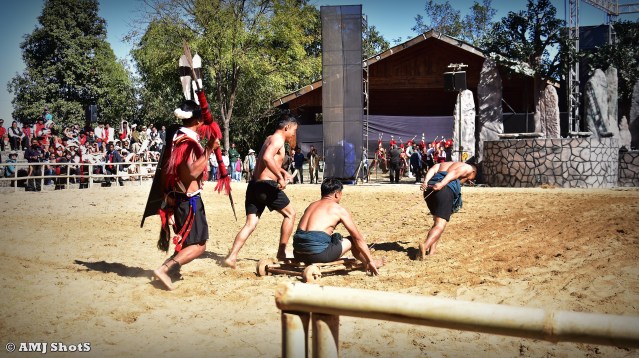

” Go-Karting “ of Ao Nagas

Traditional Go-Kart Race of Ao Nagas – Played two players in a team. One has to pull and the other has to sit and push the Go-Kart (Wooden car), towards the finish line. The car is made up with 3 small wooden wheels. As the festival’s main arena is filled with sand, the racing gets even tougher than usual.

Racially the Ao Nagas are Mongolians, therefore all Mokokchung villagers are Mongolians and is believed to have migrated from the far east ‘through’ Chungliyimti. There are five clans within the village – Pongener, Longkumer, Jamir, Atsongchanger and Kechutzar. Marriage within the same clan are prohibited and monogamy is practiced. Each clan is treated equally. The village is divided into two khels (or sectors) – the upper khel and the lower khel. Although this division is normally based on the Ao dialect(“Mongsen” and “Jungli”) spoken by the people in other Ao villages, the case is different in Mokokchung Village. Both the khels speak only “Mongsen” dialect.

3. Chakhesangs of Nagaland

‘ Chakhesang Naga ‘

Formerly known as the Eastern Angami, the present Chakhesang is one of the most progressive and remarkable tribes of the Naga families. The three syllables: Cha-Khe-Sang represents Chokri, Kheza and Sangtam people respectively. The recognition of Sangtam as a separate tribe did not disturb the original word – Chakhesang- till today. It is obvious that the pioneers of the formation of Chakhesang tribe had in mind the existence of diverse sub-tribes (communities) within it. No other Naga tribe matches Chakhesang tribe in its composition inter weaved with many communities. It is not just Kheza and Chokri people who are Chakhesangs. Along with them are the smaller communities like Poumai (Sapuh) predominantly settling in four villages under Razeba Range and in Pfutsero town. There are some Sumi (Sema) villages which fall under Chakhesang tribe. In some Chakhesang villages, one also will find Rengmas and pochuris. Therefore, Chakhesang is a conglomeration of Kheza, Chokri, Poumai, Sumi, Pochuri and Rengma. One can also trace the origin of few Tangkhul families as in Jessami. This made Chakhesang a unique tribe among the Naga family.

Entrance Gate of Chakhesang Morung

With diversity in its social composition, there are different dialects spoken among the Chakhesang people. Apart from English and Nagamese, naturally Chakhesang people could easily converse in other tribes’ dialects/languages. They use Angami’s Tenyidie Bible and Tenyidie Hymn Book as official language in the Church. It provides them easy means of communication with the Angamis. Many Chakhesangs are conversant with Poumai and Mao dialect too. Others are equally comfortable with the dialect of Sumis, Rengmas and Tangkhuls. With all these advantages, it is not a surprise that this tribe has rich traditional folklores, songs and other traditional practices. The other uniqueness of this tribe is its geographical location. It has its border with the land of Mao (Tobufii, Shajouba, Chowainu), Poumai (Tunggam, Tungjoy, Liyai, Katafiimai, Laii), Tangkhul (Jessami area), Sumi (Satakha-Poghoboto Area), Angami (Kedima-Chakabama area) and Pochury. Hence, it has easy access to many neighbouring tribes both in Manipur and Nagaland.

Chakhesang Morung

With all of the above privileges, Chakhesang people are progressing in all spheres of life: social, political and religious life. Being neighbours to many tribes and diverse in its social composition, and conversant in many dialects, they are readily accepted by others. This, apart from hard labour, is the reason why you find many Chakhesang leaders in the churches and in civil society. They are also contributing many good leaders to the state politics.

Chakhesangs are simple yet possess great sense of humour and love cracking jokes

Majority of Chakhesang people are hard working and economically self reliant. Chakhesang tribe might at the top when it comes to mixed marriages with other tribes. One can look to this tribe as the future model of Naga society.

The skull of an Indian Bison (Wild Buffalo) – On the walls of Chakhesang morung

For a foodie, particularly if one happens to be a non- vegetarian, this is a real paradise – Look at those slices of Smoked pork hanging from the ceiling of a Chakhesang morung and filled bamboo cups with rice beer, arranged on the ground.

A traditional Chakhesang breakfast. You can try these in temporarily arranged restaurants near these morungs.

Traditional lunch of a Chakhesang consists of Rice, Sliced bamboo shoots, Smoked pork, Boiled vegetables, King Chilly chutney, Dry colocasia etc. with a cup of rice beer.

Another Chakhesang showing his traditional Shawl, which is made out of the stinging fabrics from Nettle leaves. The weavers have put so much effort in creating this beautiful vibrant shawl with the most gentle precision. According to the Chakhesang custom, this shawl is worn only by men of the high class or those who have done something honorable for the society like holding feasts for the entire village. The patterns are added in batches as the number of feats they hold increases. It is said that each batch of embroidering the motif should be completed within a single day before the sun sets.

In earlier days, Chakhesangs and Khiamniungans were the only two Naga tribes producing yarns made out of Nettle plants for making their clothes.

” Thbevo Do “ – Chakhesang Women showing their traditional art of Yarn production from Nettle leaves. The fibre, extracted from stinging nettle barks and transformed it into clothes like shawl and sarong (mekhala) during olden days, before they came into contact with the outside world.

Stinging nettle does not sting after being put under a series of treatment but it is a herculean task. It takes almost a year to weave a shawl (including the overall process).

Nettle plant is harvested and left to dry for 4-5 days so that the thorny stinging bark can be stripped from the stalk. The long nettle strips are then split into narrow slivers before boiling in water along with ashes to break down the fibre and make it flexible. The fibre is then pounded on a stone surface with wooden clubs until it is softened and easily separable. The fine nettle strands are then twisted and reeled into hanks. After this treatment, the thread is bleach-bathed in rice starch, dried in the sun and then rolled into a ball. The refined fibre is finally ready to be used for weaving beautiful clothes.

For Chakhesangs, a new year of activities begin with the arrival of spring; all activities related to sports and entertainment that begin after the harvest, cease along with the Tsukhenye festival. The festival lasts for four days in the first week of May – on the first morning, the village priests sacrifices the first rooster that crows. The men folk purify themselves by bathing in a designated well where no women are allowed. After bathing they invoke the almighty for strength, long life, good harvest etc. Another important festival of Chakhesangs is the Sukrenye festival, which happens on the 15th day of January and lasts for a period of 11 days. It is a festival of sanctification and is a form of baptism in the Chakhesang culture. Ceremonies and rituals performed at the time of the festival are religious in nature. The first few days are spend in the joyous preparations for the main events and feast. People pray to the Almighty to bless and purify their souls and hence the initiation of various rituals for the purpose is carried out. Runye Lu is such a folk song, sung during festival times of Chakhesangs…..

“Ronye Lu” is an emotional folk song describing the emotions and tragedies of a villager, who is facing many problems in his life. Folk dance can be an art, ritual or recreation. It goes beyond the functional purposes of the movements used in work or athletics in order to express emotions, moods or ideas; tell a story; serve religious, political, economic, or social needs; or simply be an experience that is pleasurable, exciting, or aesthetically valuable.

Folk dramas are integral part of the Chakhesang tribe. Ancient myths, love stories, heroisms etc can be the theme of these folk dramas. One such folk drama is Tekhezuso….

Chakhesangs performing a folk drama or enactment related with their lives in the villages – Tekhezuso

During this folk drama Tekhezuso, Chakhesangs gathered around the leader in circles and listen to him.

Tekhezuso – A folk drama by Chakhesangs. It is a traditional assembly held every year during the Run time festival which falls in the month of December.

4. Chang Tribe of Nagaland

‘ Chang Naga Warrior ‘

Chang Naga is one of the recognized Scheduled Tribe in Nagaland. The tribe was also known as Mazung in British India. Other Naga tribes know the Changs by different names including Changhai (Khiamniungan), Changru (Yimchunger), Duenching (upper Konyak), Machungrr (Ao), Mochumi (Sema) and Mojung (lower Konyak).

According to oral tradition, the Changs emerged from a place called Changsangmongko, and later settled at Changsang. The word Chang is said to have been derived the word Chognu (banyan tree), after a mythical banyan tree that grew at the now-abandoned Changsang. Another theory says that the Chang migrated to present-day Nagaland from the east, and therefore call themselves Chang (“Eastern” in the local dialect). Some Changs also claim the Aos as their ancestors.[5] The Chang folklore is similar to that of the Ao.

An old Chang warrior with fancy sea shell earrings and colourful beaded necklaces, getting ready for the cultural sessions in their morung.

The traditional territory of the Changs lies in the central Tuensang district. Their principal village was Mozungjami/Haku in Tuensang, from which the tribe expanded to the other villages.

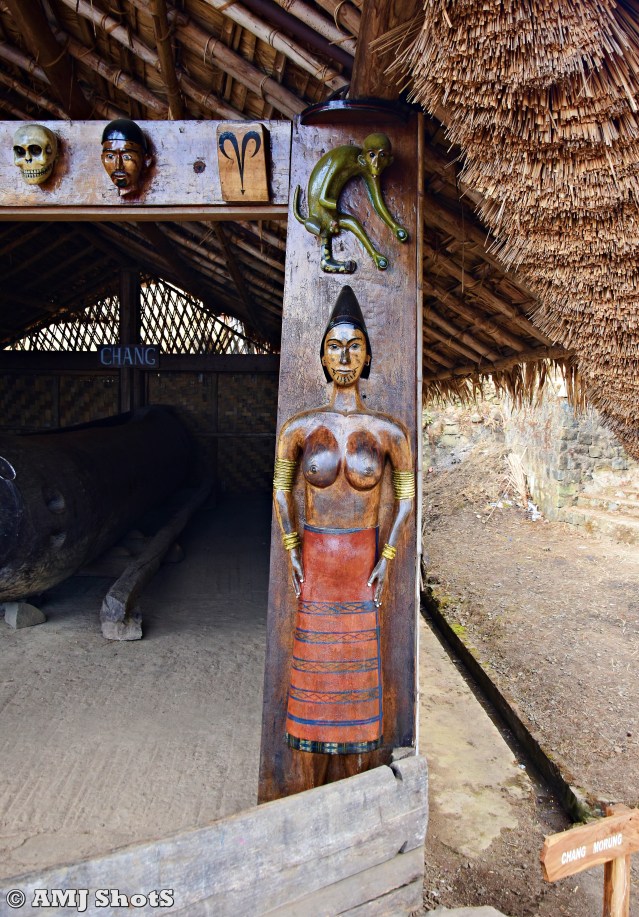

Traditional Morung of Chang Naga – Back in the days, the tribesmen would carve a nearly-possible image of their deceased family members on the wooden frames of doors and windows, as a memory; the only way to remember them.

Wooden Sculpture of a Chang lady. And also, you can see the sculptures of human skull, severed head of an enemy, a green monkey.

The Chang, like several other Naga tribes, practiced headhunting in the pre-British era. The person with maximum number of hunted heads was given the position of lakbou (chief), who would settle the village disputes. He was entitled to maintain special decorative marks in his house, and to wear special ceremonial dress during the festivals. After the headhunting was abolished, the village disputes were resolved by a council of informally elected village leaders. Such councils also selected the fields for jhum cultivation, and fixed the festival dates. The Changs constructed a platformed called “Mullang Shon” in the center of the village, which would serve as a public court. Issues such as village administration, cultivation, festivals, marriages and land boundaries were discussed on this platform. The official interpreters (dobhashis) are recruited from important villages by the Deputy Commissioner of the district. These dobhashis help settle tribal cases, and fix the fine rates for some of the cases. The traditional village judges (youkubu) also help resolve the land disputes.

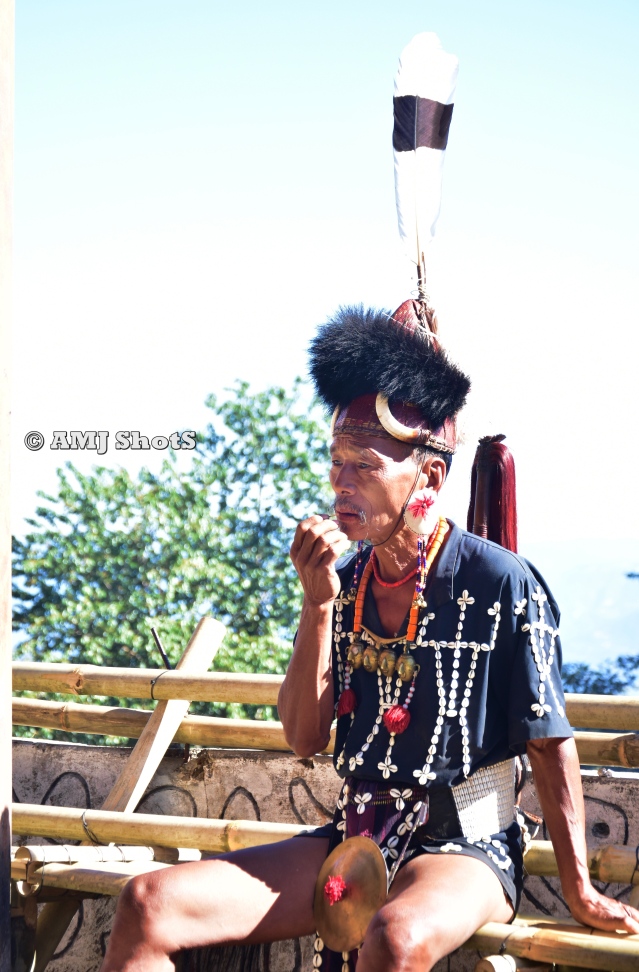

A Chang Naga in his traditional dress and ornaments; includes dark coloured cotton shirts stitched with small sea shells, long necklaces with broad beads and tribal head-shaped metal lockets. The head dress is a coronet made out from leathers and decorated with woolen fabrics and hornbill feathers.

After the advent of Christianity, several Changs have adopted modern clothing. The traditional Chang dress features distinctive shawl-like garments and ornamented headgear. Chang shawls “surpass all the Naga shawls in beauty and eye-catching patterns”. The shawl designs are different for different age groups and clans. Mohnei, a cowrie-ornamented shawl, could be worn only by a man who had taken more than 6 heads.

Chang Nagas proudy displaying their soulful War cry during the roll calling process in the main arena.

The Changs speak the Chang language, which belongs to the Tibeto-Burman family. Nagamese is used for communicating with the outsiders. The educated Changs also speak English and Hindi languages.

The men folk of Chang tribe playing log drum ‘Antimonyu or Sungkong’ , as a display for the tourists.

This log drum is very integral part of Naga life. This is created out of huge tree trunk sometime going upto 30 to 40 mts. in length and 5 to 6 feet height. The drum is flattened from the bottom to place it on the ground firmly and from the top through carvings a hollow is made and on hitting from top the sound emits. Some times those are highly decorated with human motif. It is not only restricted to create martial music but on all occasions from birth to death from festivals to the death news and from announcing time of the elders meetings to declare emergency when the rival group attacks are the function of this log drum.

As such there is no formal codification of these sound beats. But through oral tradition everybody understands as a peculiar sound emits on all different occasions. This is more on the communication mode than a simple ritual of Naga people. The traditional instruments also include xylophone, various drums (made by stretching animal hide), bamboo trumpets and bamboo flutes.[3] The traditional instruments have been replaced by guitar among the modern Changs.

Let’s see the moments of a traditional ritual followed by Chang Nagas in selection and pulling of log drum from the wild – ” Tongten Senbu “……

‘Tongten Senbu’ (Pulling of log drum) – This is a very elaborate process. First of all one of the Naga man has to volunteer to donate a tree from his own forest area. Then youth go to cut the tree and after performing a ritual they start the tree-falling process.

‘Tongten Senbu’ – Only tool they use is Dao. Then for seven days the process of bringing tree from forest to village starts. These are brought through indigenous process.

‘Tongten Senbu’ – In all these days women and girls bring foods and drinks for the youth who toe the log. Its almost a festival for them.

‘Tongten Senbu’ – Once the log is brought to the village expert woodcarvers create the drum and do the traditional art work on them.

‘Tongten Senbu’ – After a small ritual the drum is placed near the Morung or dormitary for regular use.

Chang Nagas leaving the main arena after performing ‘Tongten Senbu’ process.

The traditional Chang cuisine is non-vegetarian, and comprises a variety of meats and fish. Rice is the staple food of the tribe. let’s see their traditional way of fishing – ” Kaishi Lakshibu ” ….

“Kaishi Lakshibu” – During winter season, after the hardships of harvesting, the villagers engage in many celebrations. The major one is this Kaishi Lakshibu. The whole village decides to go for fishing in nearby river, using an indigenous technique called ‘Ejung Tsen’. For that, they uses a special type of local fruit from the wild – Kai. After fixing the date for fishing, the Chieftain sends boys to pick up Kai fruits from wild. Then, the villagers go to the river with bamboo pots and the men folk immerse these pots in water and fill them with wild Kai fruits. After that, they start grinding those fruits and pouring water into the mix. This process turns the river water in to reddish colour. Slowly, the fishes get dizzy and stays still above in water. This makes the catch easier. Women folk are responsible for catching these fishes. The folk songs sung by men folk during this occasion translates into ” We pay our enemies with fishes in the river. We are sending disaster to you. Oh, fishes… you have no way to escape because the enemies had surrounded you and you are feeling dizzy also. All fishes….. please, converge”

Tribal chief of Changs leaving the main arena after performing Kaishi Lakshibu – Traditional way of fishing among Chang Nagas.

Milk, fruits and vegetables were not a major part of the traditional Chang food habits, but have been adopted widely in the modern times. Rice beer used to be of high social and ritual importance, but has largely been abandoned after the conversion of Changs to Christianity.

Naknyu Lem is the major traditional festival among the six festivals of the Changs. According to the Chang mythology, the ancient people had to remain inside their homes for six days due to extreme darkness. Naknyu Lem is held to celebrate the light on the seventh day. On the first day, the domestic animals are slaughtered, the villages are cleaned, and firewood and water are stocked.

On the second day (Youjem, dark moon day), the tribals exchange gifts and food items, and play sports like, top-spinning, tug-of-war, high jump, long jump, climbing of oiled poles, and grabbing big lumps of cooked meat hung in rows along a bamboo rope strung at height. Women play a musical instrument called kongkhin. The paths and the houses are decorated with leaves, and a shrub called Ngounaam is planted in front of the house to ward off the evil spirits. At sunset, seeds called Vui long are buried inside the rice husks and burnt around the house. Fragments of the exploding seeds moving away from the house are considered a good omen. If the fragments bound back towards the house, it is a bad omen. People don’t go out of their homes at sunset, as it is believed that the spirit Shambuli Muhgha visits the village, and harms anyone outside the house. On the third day, the village and the approach roads are cleaned. Later, the paths leading to the fields and neighbouring villages are cleaned.

Most of the Naga folk songs are related to the harvesting and sowing seasons, in connection with their agri fields. ” Sekmou Chemmoubu Otuang Onet “ is one such rhythmatic song sung by the Changs to ease up their tiring workloads and pace up the cultivation process, while working in their agri lands…..

Chang Nagas singing Sekmou Onet, a cultivation folk song while enacting the tilling process in their agri lands.

The village Chief encourages men folk to pace up their working by performing the folk cultivation song – Sekmou Onet

Men and women folks of Chang tribe performing a folk song with dance – ‘Sukem Chia’. This song is sung during celebratory occasions where the wealthy citizens of their village would offer Mithun for the festive season.

Women folks of Chang tribe dressed up in their traditional attire to perform a folk song – ‘Sao Chia’

The traditional Chang society is patrilineal, and the males inherit the land and the positions of authority. Nuclear families are predominant in the Chang society. The marriage is called chumkanbu, and remarriages are permitted.

5. Garo Tribe of Nagaland

A moment from the ‘Quarrel Dance of Garo Tribe’

Garos are an indigenous Tibeto-Burman ethnic group from the Indian subcontinent, notably found in the Indian states of Meghalaya, Assam, Tripura, Nagaland, and neighboring areas of Bangladesh, who call themselves A·chik Mande (literally “hill people,” from a·chik “bite soil” + mande “people”) or simply A·chik or Mande. They are the second-largest tribe in Meghalaya after the Khasi and comprise about a third of the local population. The Garos are one of the few remaining matrilineal societies in the world.

The Garos are mainly distributed over the Garo Hills and Khasi Hills of Meghalaya, Ri-Bhoi Districts in Meghalaya, several districts such as Karbi Anglong districts of Assam and Dimapur district in Nagaland State. Their substantial numbers (about 200,000) are also found in few districts of Bangladesh which includes its capital Dhaka. It is estimated that total Garo population in India and Bangladesh together is about 1 million. Garos are also found scattered in the Indian state of Tripura. Garos form minorities in West Bengal, as well as in Nagaland. The present generation of Garos forming minorities in these states of India do not speak the ethnic language anymore.

A traditional Garo Morung – Garo Nokpante

Large part of the Garo community follow Christianity, with some rural pockets following traditional animist religion known as Songsarek and its practices. Their ancient animistic religious beliefs and practices consists with deities who must be appeased with rituals, ceremonies and animal sacrifices to ensure welfare of the tribe. Garo tribal religion is popularly known as Songsarek. Their tradition “Dakbewal” relates to their most prominent cultural activities.

Garo Nokpante – In the Garo habitation, the house where unmarried male youth or bachelors live is called Nokpante. The word Nokpante means the house of bachelors. Nokpantes are generally constructed in the front courtyard of the Nokma, the chief. The art of cultivation, arts, and cultures, and games are taught in the Nokpante to the boys by the senior boys and elders.

Garo language belongs to the Tibeto-Burman language family. The language was not traditionally written down; customs, traditions, and beliefs were handed down orally. It is believed that the written language was lost in its transit to the present Garo Hills. Garo language/script was written on the skins of cows; while on the way their ancestors faced famines so they cooked them. The written language/script was lost. The Garo language has dialects – In Bangladesh, A·beng is the usual dialect written in Bengali script, but A·chik is used more in India. A·we has become the standard dialect of the Garos written in Roman script. A·we is used in Garo literature and, hence, for the translation of the Bible. The Garo language has some similarities with Boro-Kachari, Dimasa, and Kok-Borok languages. The modern official language in schools and government offices is English.

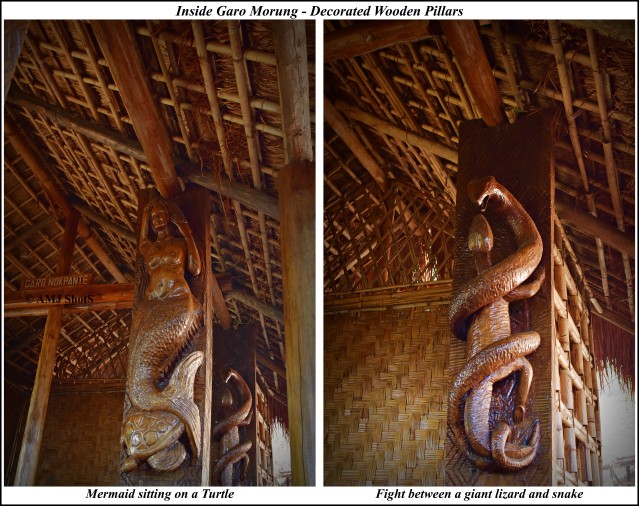

Inside Garo Nokpante – Wooden sculpture of a Two-headed man (facing opposite to each other)

According to one oral tradition, the Garos first immigrated to Garo Hills from Tibet (referred to as Tibotgre) around 400 BC under the leadership of Jappa Jalimpa, crossing the Brahmaputra River and tentatively settling in the river valley. The Garos finally settled down in Garo Hills (East-West Garo Hills), finding providence and security in this uncharted territory and claiming it their own.

Inside Garo Nokpante – At the end of one of the wooden frames, the shape of a mountain goat’s head is carved out.

The earliest written records about the Garo dates from around 1800. They were looked upon as bloodthirsty savages, who inhabited a tract of hills covered with almost impenetrable jungle, the climate of which was considered so deadly as to make it impossible for a white man to live there. The Garo had the reputation of being fierce headhunters, the social status of a man being decided by the number of heads he owned. In December 1872, the British sent battalions to Garo Hills to establish their control in the region. The attack was conducted from three sides – south, east, and west. The Garo warriors (Matgriks) confronted them with their spears, swords, and shields. The battle that ensued was heavily unmatched, as the Garos did not have guns or mortars like the British Army.

Garos are one of the few remaining matrilineal societies in the world. The individuals take their clan titles from their mothers. Traditionally, the youngest daughter (nokmechik) inherits the property from her mother. Sons leave the parents’ house at puberty and are trained in the village bachelor dormitory (nokpante). After getting married, the man lives in his wife’s house. Garos are only a matrilinear society but not matriarchal. While the property is owned by women, the men govern the society and domestic affairs and manage the property.

Their staple cereal food is rice. They also eat millet, maize, tapioca etc and rear cows, goats, pigs, fowls, ducks etc. and relish their meat. They eat other wild animal like deer, bison, wild pigs etc. Fish, prawns, crabs, eels and dry fish are a part of their food. Their jhum fields and the forests provide them with vegetables and roots for their curry. Bamboo shoots are esteemed as a delicacy. They use a kind of potash in curries, which they obtained by burning dry pieces of plantain stems or young bamboo locally known as kalchi or katchi. After they are burnt, the ashes are collected and dipped in water; they are strained in conical shapes in a bamboo strainer. Besides other drinks, country liquor plays an important role in the life of the Garos.

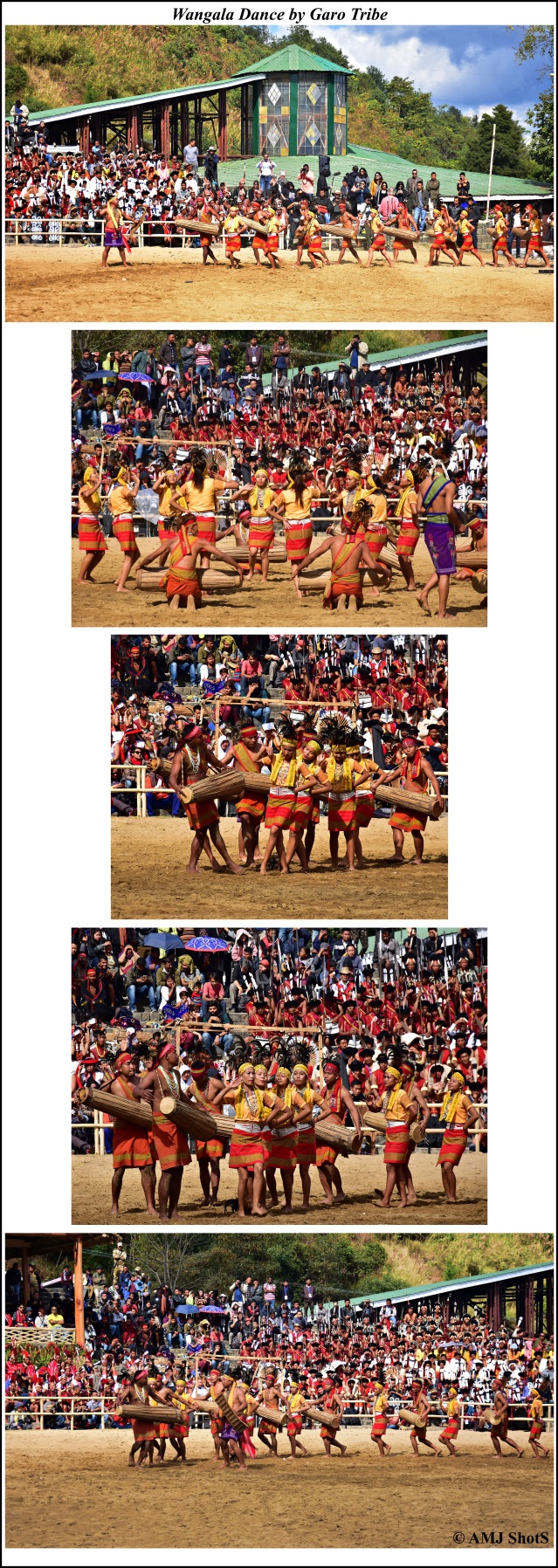

Garo festivals are based on the agricultural cycle of crops. The harvesting festival Wangala, also known as the 100-Drum festival, is the biggest celebration of the tribe happening in the month of October or November every year. It is the thanksgiving after harvest in the honor of the god Saljong, provider of nature’s bounties. Beautiful Garo girls known as nomil and handsome boys pante take part in ‘Wangala’ festivals. The pantes beat a kind of long drum called dama in groups and play bamboo flute. The nomils with colorful costumes dance to the tune of dama and folk songs in a circle. Most of the folk songs depict ordinary Garo life, God’s blessings, beauty of nature, day-to-day struggles, romance, and human aspirations.

” Wangala Dance ” of Garos – Also known as The Hundred Drums Festival or Wanma Rongchua. In this post harvest festival, they give thanks to Misi Saljong (also known as Pattigipa Ra’rongipa), the sun god, for blessing the people with a rich harvest. Chambil Mesaa or the Pomelo Dance are performed during Wangala festival. Dama Gogata, the dance with drums, flutes and assorted brass instruments by men and women in colourful dresses and proud headgear – a picture which is synonymous with visuals of Wangala – is performed on the last day of the days-long celebration

Rugala (Pouring of rice beer) and Cha·chat So·a (Incense burning) are the rituals performed on the first day by the priest, who is known as ‘Kamal’. These rituals are performed inside the house of the Nokma (chieftain i.e. the husband of the woman who holds power over an a’king) of the village. Wangala is traditionally celebrated for two to three days – or up to a week – by two or three collaborating villages; though recently it has been celebrated for one day in metropolitan areas as an attempt to conserve the ancient heritage of the Garo tribe and to expose the younger generation to their roots.

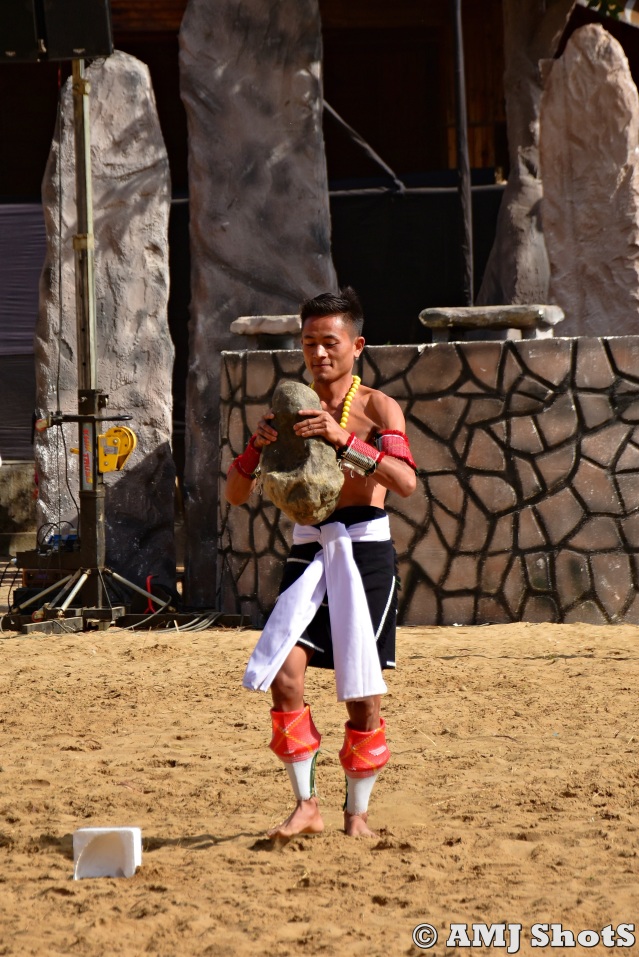

‘Ro’ong Dea’ – An indigenous stone lifting game of Garos

Ro’ong Dea – This loosely resembles the modern weight lifting. A smooth round stone weighing about 100 kg or more is placed among the spectators. Anybody from among the spectators can come forward and give a try in lifting the stone. The participants try to lift it as high as possible. Needless to say that the player, the participant that lifts it highest, is the winner and is deemed to be the strongest man in the village.

A Garo Naga challenging the members of other tribes and audiences to participate in Ro’ong Dea challenge.

Praising the Winner – A Zeliang Naga successfully completes the Ro’ong Dea challenge.

Garo Ornaments includes Nadongbi or sisa (made of a brass ring worn in the lobe of the ear), Nadirong (brass ring worn in the upper part of the ear), Natapsi (string of beads worn in the upper part of the ear), Jaksan (bangles of different materials and sizes), Ripok (necklaces made of long barrel-shaped beads of cornelian or red glass while some are made out of brass or silver and are worn in special occasions), Jaksil (elbow ring worn by rich men on Gana ceremonies), Penta (small piece of ivory struck into the upper part of the ear projecting upwards parallel to the side of the head), Seng·ki (waistband consisting of several rows of conch-shells worn by women) and Pilne (head ornament worn during dances only by women).

“Quarrel Dance” of Garo tribe – This dance reflects the quarrel between the clans of Garos; Sangma (Intelligence) and Marak (Power). Two persons holding a millam (sword) and sepi (shield) try to overpower each other. After the feud, the women folk performs a folk dance and making of peace follows.

One another indigenous game performed by Garos was ‘Jaktongsika’ – A test of strength between two men of Garo tribe…..

Jaktongsika – An indigenous game showing the test of strength between two Garo men. The game is played inside a circle, guided by tribal referee. The participants are allowed to use their hands only. They need to push the opponent out of the marked circle.

Garos have their own weapons. One of the principal weapons is a two-edged sword called mil·am made of one piece of iron from hilt to point. There is a cross-bar between the hilt and the blade where a bunch of ox’s tail-hair is attached. The other types of weapons are shield, spear, bow and arrow, axe, dagger, etc.

Garo musical instruments can broadly be classified into four groups. Idiophones (Self-sounding and made of resonant materials) like Kakwa, Nanggilsi, Guridomik etc. Aerophone (Wind instruments, whose sound come from air vibrating inside a pipe when is blown ) like Adil, Singga, Sanai, Kal, Bolbijak etc. Chordophone (Stringed instrument) Dotrong, Sarenda, Chigring or Bagring etc. Membranophone (With skins or membranes stretched over a frame) Am·being Dama, Chisak Dama, Atong Dama etc.

6. Kachari Tribe of Nagaland

Kachari Women performing their folk dance – “Bai Dima”